The UK government is intent on removing planning permission requirements surrounding fracking. Yet with Energy Minister Claire Perry demanding a “line of sight to commerciality”, evidence from the US shows fracking almost never makes any money.

The Economist put it bluntly: “America’s shale gas firms don’t give a frack about financial returns”

Now, the economic rationale of the UK’s shale firms has been further shaken by a series of economic and political tremors: gas demand is falling; foreign companies are increasing exports; renewables keep getting cheaper; even Jeremy Corbyn now says he’ll ban the process.

UK Fracking has never made any money. In fact, fracking has never made any money- anywhere (see below). And it’s unlikely that it ever will. Here’s why:

US Frackers don’t make any money

“With the exception of airlines, Chinese state enterprises and Silicon Valley unicorns, shale gas firms are on an unparalleled money-losing streak.” (The Economist)

Market analysis from several leading publications suggest virtually no US natural gas or oil fracker has ever delivered any return on investment – at all.

The Wall Street Journal provides the following: “energy companies [since 2007] have spent $280 billion more than they generated from operations on shale investments.”

In this country, an eruption of cash once shot skywards before splashing down upon the vainglorious scheme to get fracking started.

Today UK frackers are teetering on the brink of bankrupcy.

Third Energy (owned by Barclays) – who once guzzled £50m in an attempt to frack Yorkshire – is almost bust and can’t find a buyer. Raithlin Energy – again intent on chewing up the Yorkshire countryside – has a debtor tab of £34m, “a material uncertainty,” says auditor KPMG, “on the Company’s ability to continue as a going concern”. And fracking wunderkind Cuadrilla has spent more than £100m at their Lancashire site near Blackpool. A company barrister told a recent court case the company was spending £94,000 a day on attempts to get Preston New Road fracked.

Any gas produced, anywhere? Nope.

US frackers rely on continual debt to keep going

But all this is OK. Indeed, US frackers splurged up to $554 billion between 2014 and 2022.

That’s a big number. That’s a fashionable number. That’s the kind of number that – if you were you a Conservative politician – maybe you could ignore those thousands of complaints. In fact, maybe you could kneel and pray that the likes of Cuadrilla can quickly bore themselves out of their financial hole and perhaps pay some tax with which you can impress your consituents.

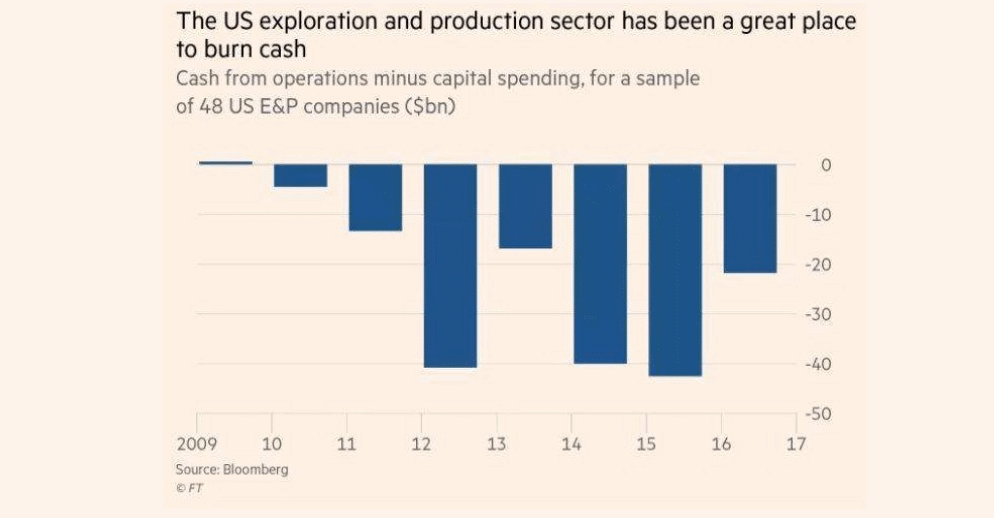

Yet the Financial Times recently dug into the figures of 48 US natural gas frackers, and worked out how much money this motley crue is actually making. The answer is: none at all:

So how does the natural gas fracking business actually work?

It turns out that – to keep themselves going – fracking companies borrow. They borrow a lot. They borrow so much, in fact, they are generating fears of a second financial crisis.

And this is the way the fracking substrata crumbles: companies buy time by paying debt interest with more debt. Hundreds of billions of dollar of loans are building up, the next paying for the last, surely the very definition of a ponzi scheme.

The uncomfortable truth is that shale wells generate insufficient revenue to pay off interest and principal. Instead, US shale gas companies must continually take on debt – and pay their responsibilities with the money they borrow.

Gas Demand Falls, Competition Rises = prices fall

But the economic rationale that holds up UK fracking is also contaminated:

1. Gas usage has fallen for years. EU gas demand is 10 percent less than it was in 2007. Indeed, the standard European price of gas is at half its 2013 level. It’s unlikely a gas shortage will manifest to life raft those ailing balance sheets. More and more (non UK) producers have gas on the market – which doesn’t augur well for domestic competitiveness.

2. Renewables are getting cheaper, with large-scale wind and solar 50-60% cheaper since 2013.

3. The UK can’t frack cheaply, since most reserves sit under population centres. Funnily enough, these centres are remarkably unwilling to submit to the various cowboy operations forced upon them and who demand they give up the integrity of their substrata. And all the various conflicts this throws up – legal cases, regulatory obstacles, planning enquiries, public enquiries, public relations men and women – are expensive. Sussex fracker UKOG, for example, maintains it spent £1m on evicting a protest camp two years ago, and that’s only the start of it.

Labour in 2021 and Brexit are significant new Risks

Finally: significant new risks surround shale projects. These risks didn’t exist in 2011 when the process was first mooted.

If Labour wins in 2021, for example, the party has said it’ll ban fracking. Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell and several other shadow cabinet members have selfie’d with protesters outside Cuadrilla’s Preston New Road site. Most unions deplore fracking. And Jeremy Corybn has made himself plenty popular on social media pledging to bin it.

A Labour government will ban fracking immediately. pic.twitter.com/QJQrs7blYJ

— Jeremy Corbyn (@jeremycorbyn) October 22, 2018

Even with a government that crawls on its knees to favour the shale process, it has been heinously difficult to find any sort of elixir. If Labour comes to power then all those hundreds of millions of liabilites on company balance sheets stands to be written off.

And that’s not to mention Brexit. INEOS (the UK’s largest potential fracker) has signaled that if the UK leaves the EU with no deal then its entire operation will be shut down.

Endgame

And so this is the turbulent gamble into which the government wants us to plunge.

Watched over by their Conservative overlords, various UK start ups eye their US cousins troughing on debt. They dream of drilling hole after hole, only dimly aware of the financial peril towards which it leads them.

One day – they daydream, clicking their biro against the portacabin window – they’ll be chased by City men, London men, who offer bond after new bond, paying off all those irritating creditors, and then they’ll criss cross the country with their thrusting pipes, brave frontiersmen of an energy transition that is – in reality – little more than a desperate thrashing of what will soon be gone.

The US shale boom has indeed produced success: a record amount of oil and gas production. But the economic rationale on which it is based – not to mention the excremental toxicity of the whole thing – is rotten to the core.

Thanks to Jeremy Legget for the spur for this post, see his original here